Douglas Allsop [GB] · * 1943 in London, lives and works in Berlin

Picture gallery oneΛ top

Selected works

Photo credits: 1 - 6 dr. julius | ap, at Anschauungen, 2013 · 7 - 11 Niklas von Bartha at Das Kleine Museum: Douglas Allsop, Weissenstadt, 2012 [7], Bartha Contemporary: From Here, London, 2014 [8 – 10]

Picture gallery twoΛ top

Selected installation views

Photo credits: 1 - 6 dr. julius | ap · 7 - 11 Nadine Poulain

Exhibition list. Λ top

Solo exhhibitions. selection as from 2000

2018

reflexion, Galerie Lindner, Vienna, Austria

'differing views', retrospective, RAUM SCHROTH, Soest

2017

'douglasa allsopa', w Galerii AT, Poznan, Poland

2016

'fresh windows',exchange rate, Brooklyn, New York, USA

2015

‘metric’, Douglas Allsop / Riki Mijling, dr. julius | ap, Berlin. Germany

‘blind screen’, sleeper 1, reiach and hall architects, Edingburgh

‘nicht nur Black and White’, Douglas Allsop / Tom Mosley, Städtisches Museum Gelsenkirchen, Germany

2014

‘from here’, Bartha Contemporary, London

2013

‘Douglas Allsop / Peter Weber’, Galerie Renate Bender, Munich, Germany

‘Anschauungen’, dr. julius | ap, Berlin, Germany

2012

‘Farben und Reflexionen’, Douglas Allsop und Bim Koehler, Das Kleine Museum, Weißenstadt, Germany

‘reflexionen / transparenz’, Douglas Allsop und Dirk Salz, Galerie Bernd A.Lausberg, Düsseldorf, Germany

2010-11

‘undsoweiter’, Stiftung für konkrete Kunst, Reutlingen, Germany

2010

‘douglas allsop’, hebel_121, Basle, Switzerland

2009-10

‘façade’, Olschewski & Behm, Frankfurt, Germany

2009

‘ Fast surface, Blind screen and Reflective Editors.’ Douglas Allsop, Professor of Fine Art, Letherby Gallery, Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design, University of the Arts, London

2008

‘Blind Screen’, Städtische Galerie Villa Zander, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany

‘fenster’, projektraum4, Kim Behm, Mannheim, Germany

‘blind spot’, Bartha Contemporary’, London

2007

‘Douglas Allsop. View’, Kunstverein Eislingen, Eislingen, Germany

2006

‘Douglas Allsop’, CENTRE D’ARTS, plastiques et visuels, Lille, France

‘binnen/buiten - Douglas Allsop’, Mondriaanhuis, Amersfoort, Netherlands

2005

‘Douglas Allsop – nine reflective editors’, Stiftung für konkrete Kunst, Reutlingen, Germany

2004

‘Douglas Allsop at KettlesYard’ , University of Cambridge, Cambridge

2003

‘Two Views’, Gallery N. von Bartha, London

2002

Gallery N. von Bartha, London

2002

‘Douglas Allsop - seven sequential spaces’, Southampton City Art Gallery, Southampton

2001

Douglas Allsop – Zeichnungen, Objekte und Installationen 1971-2001’, Städtisches Museum, Gelsenkirchen and Emschertal Museum, Herne,

2000

‘Aus den Fenstern’, Versandhalle, Stadtpark Insel, Grevenbroich, Germany

Group exhibitions. Selection as from 2000

2015

‘Black and White II’, Galerie Renate Bender, München, Germany

Stiftung Konzeptuelle Kunst Sammlung Schroth, Hellweg Konkret No 4‘precise feelings’ Museum Aahlen, Museumplatz, Aahlen, Germany

Stiftung Konzeptuelle Kunst Sammlung Schroth,‘business’, Assembly House, Saarbrücken, Germany

2014

‘Double Blind’, 4 Windmill Street, London

‘Private View. By Appointment’, dr. julius | ap, Berlin, Germany

‘uncertain visions’, six films curated by Arata Mori: with Yokiko Okura, Liav Gabay, Stepanie Iluz, Kush Badhwar and Nadine Poulain. Berlin

‘Wünderkammer’, Bartha Contemporary, London

‘Faszination Farbe’, Galerie Renate Bender, München, Germany

‘TECH. ART. INTERSECT.’ dr. julius | ap, Berlin, Germany

2013

‘Jubiläumsfeier’, 10 jahre Galerie Bernd A. Lausberg, Düsseldorf, Germany

2012

‘neue druck und zeichnung’, Sammlung Schrott, Soest, Germany

‘Neuzugänge IV, INFORMATION’, Sammlung Schroth, Soest, Germany

2011

‘Konkrete Abstraktion’, Galerie Bernd A. Lausberg, Düsseldorf, Germany

‘portability and network’, SPACES, Cleveland, Ohio, USA

2010

’potpourri – intermezzo 02’, Olschewski und Behm, Frankfurt, Germany

‘geometrisch-abstrakt-kinetisch, Galerie Emilia Suciu im Kunstverein Speyer,

Germany

‘beyond painting’, Lausberg Contemporary, Toronto, Canada

2009

‘hommage an eine gründergeneration’, Bauhaus 2009, Forum konkrete Kunst, Erfurt, Germany

‘upside down/inside out’, Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge, Cambridge

‘mehr licht’, Olschewski & Behm, Frankfurt, Germany

‘Die Farbe Bunt’, Galerie Bernd A. Lausberg, Düsseldorf, Germany

‘Parole à Voir, dialogues en noir blanc gris’ Musée des Ursulines, Macon, France

2008

‘Ahnlichkeiten-Homage à Fortuny’, Stiftung für konkrete Kunst, Reutlingen, Germany

‘nummer 1’, Olschewski & Behm, Frankfurt, Germany

‘Gegenstandlos’, Gessellschaft für Kunst und Gestaltung e.V. Bonn, Germany

‘20 Jahre’, Galerie Emilia Suciu, Ettlingen, Germany

‘Accrochage’, Bartha Contemporary, London

2007

‘Additiv, Parallel, Synchron, werke der sammlung’, Stiftung für konkrete Kunst, Reutlingen, Germany

‘Accrochage’, Gallery N. von Bartha, London

2006

‘schwarzweiß als farbe’, Galerie Bernd. A. Lausberg, Düsseldorf, Germany

‘Drawing Breath’, Jerwood Drawing Prize, Wimbledon School of Art, Wimbledon, London

‘Über Kopf’, Flottmann Hallen, Herne, Germany

‘modern 06’, Residenz München, Germany

‘horizontales, verticals, seules, art concret, Musées de Pontoise, Pontoise, Paris, France

‘Additiv, Parallel, Synchron, werke der Sammlung’, Stiftung für konkrete Kunst, Reutlingen, Germany

‘open space’ , Art Cologne 40, Internationale Kunstmarkt, Germany

2005

‘Look Don’t Think’, Broadbent Gallery, London

‘minimal –means’, 20 Jahre Kunstverein, International Jubiläumsausstellung’, Kunstverein Eislingen, Eislingen, Germany

‘Lohn der Arbeit’, Westdeutscher Künstlerbund e.V., Flottmann Hallen, Herne Germany

‘Collection–Eva Maria Fruhtrunk’, Musée de Cambrai’, Cambrai, France

2004

‘Raumkonzepte’, Peterskirche, Petersberg, und Kolloquium:‘Philosophie – Konzepte – Rezeption’, Kulturforum Haus Dacherden, Erfurt, Germany

‘Twenty-Four by Thirty’, Keith Talent Gallery, London

‘Museumsammlungen’, Studiogalerie, Emschertal Museum, Herne, Germany

2003

’10 – zehn – X’, 10 Jahre Forum Konkrete Kunst, Erfurt, Germany

‘Konstruktive Kunst aus England, Arbeiten auf Papier’, Stadtbücherei, Neibull, Germany

‘Silbentanz’, Project Z Null, Köln, Germany

‘L’abstraction géométrique vécue – rencontre entre un peintre et un collectionneur’, musée de Cambrai , Cambrai, France

2002

‘DIN Art 4’, Museum für Kommunikation, Hamburg, Germany

‘Drawings’, Sarah Myerscough Fine Art, London

‘Minimal Art – Ancient Chinese’, Gallery N. von Bartha, London

‘Accrochage zum 20ten’,Gesellschaft für Kunst und Gestaltung, eV, Bonn, Germany

2001

’The Open Drawing Exhibition’, George Street Gallery, Humberside University, Hull

‘The Drawing Exhibition – Cheltenham, Halle Carrosserie, Sierre, Switzerland

‘Artistes d’Galerie’, Galerie Victor Sfez, Paris

‘DIN Art 4’, Museum für Kommunikation, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Gallery Artist’s, Gallery N. von Bartha, London

‘British Abstact Art’, Flowers East, London

2000

’Zeit-Räume’, Städtische Galerie, Villa Zanders, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany

‘The Open Drawing Exhibition’, Pittville Gallery, Cheltenham (Prize Winner)‘MONDIALE ECHO’S’, Mondriaanhuis, Amersfoort, The Netherlands

‘Culturalities’, Kapil Jariwala Gallery, London

Texts: Alison Green - the oculist witness · Wolfgang Vomm - On the Opulence of the AustereΛ top

Alison Green - the oculist witness

There is a passage in Being and Nothingness in which Jean-Paul Sartre describes the feeling of pure consciousness experienced by training his ear and eye against a keyhole to observe a scene on the other side. In a sense, the door acts as a screen, and Sartre says that up against it his body falls away, and he becomes the act of looking. “My attitude, for example, has no ‘outside’; it is a pure process of relating to the instrument [the keyhole] to the end to be attained [the spectacle to be seen], a pure mode of losing myself in the world, of causing myself to be drunk in by things as ink is by a blotter... “1 The penny drops, of course: he hears footsteps in the hall, the observer is observed, and the whole situation changes. This is what Sartre calls “the look.” He writes: “I see myself because somebody sees me.” I am not autonomous, experiencing things in pure subjectivity [this is the ego’s illusion], but am made by the connection between myself and other people.2 In Sartre’s strange and evocative explanation, the Other makes me an object like any other object; my inside is, in fact, “nothing.” I find myself at the end of the Other’s look.

What is important for Sartre - and what makes his text a good introduction to a discussion of Douglas Allsop’s work - is that pure consciousness [Sartre calls it “the unreflective consciousness of the self,” which he also refers to as bad faith] is a specific, provisional experience we believe to exist, but it doesn’t account fully for the complicated way we perceive ourselves in the world. This special case, I would say, is analogous to works of art like those Allsop makes, works that engage and concentrate sense-perception. Works such as his, reduced in colour, shape, and material such that the details of their facture and placement initiate your experience of them, function very much like Sartre’s keyhole: the observer gets lost in a pure process of relating to the instrument, to the end of being granted an uncommon moment of self-reflection.

This introduction helps account for certain contradictions in Allsop’s recent work: the precision with which it is made and installed, and his allowance for whatever environmental effects occur; his interest in the subjectivity of experience, and the total absence of any authoring marks in the work; his use of readymade and disposable materials, and their utter opposition to entropy. These works confound critical approaches to contemporary art practices based in recent art history; they’re not Minimalism, not a Duchampian intervention into art’s institutions, not a revival of Constructivism or geometric abstraction, not a Pop-related embrace of consumerism.3 In a sense, Allsop’s works are the products of a very old set of questions - like how do we perceive and can we trust what we see? - embodied in a relatively new set of materials and contexts. They offer a concentrated visual experience, but - a little like Sartre’s t consciousness - they also insist that this experience is mediated by the specifics of the place where they are sited.

There is an old philosophical bias that artists have a special and advanced understanding of vision, and this notion was at its apogee when Allsop began his career in the mid 1960s. An episode from that period that represents a high watermark for the belief in a scientific explanation of art, and the low watermark for its misuse as a period-category is the 1965 exhibition, The Responsive Eye. Held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, it was a survey of later twentieth-century abstract art commenting on the “Op Art” phenomenon.4 The idea was that a correspondence could be made between scientific explanations of cognitive perception and contemporary works of art that “excited the retina.5” William Seitz, a veteran curator at MoMA, explained in the catalogue that:

“Stripped of conceptual associations, habits, and references to previous experience, perceptual responses would appear to follow innate laws, limited though our understanding of them might be... All forms of representation, even ideographs, signs, and symbols, also alter or deflect whatever is innate in vision.6”

Seitz wished to explain the international emergence of a whole range of “entirely abstract” art that had, as it were, cut its ties from art’s illusionistic or representational function. The optical quality of such work, like that of Josef Albers or Bridget Riley, derived from emptying out all pre-existing forms of representation. What was left was colour, tone, shape, pattern, rhythm, balance, aspects essential to art but usually subordinate. With narrative or subjective content gone, the eye-mind could wonder freely at its own activity. A diagonal line, it turns out, feels very different from a horizontal one. Colour feels too, but not absolutely, since red, for example, seems categorically different when next to blue than next to black. The fact that these effects are to an extent measurable, and in the case of some artists’ work, devices quite easy to replicate, only strengthened Seitz’s belief that there was something essentially visual about this kind of art. He asked, “What are the potentialities of a visual art capable of affecting perception so physically and directly?”7

We well may ask the same question in relation to Allsop’s work, even as we know that history has intervened in the interim to insist that vision - or more specifically, art - is a construction of culture, not nature.8 Critical theory has concentrated on the “turn to language,” and shown us that looking at art is not a natural activity at all. This “eye” that connects us to a sensual, bodily experience is a highly acculturated instrument, trained by sustained visual study and supported by institutions like museums, books and critical discourse. Nonetheless, little work has been done regarding questions of vision and visuality within the condition this knowledge grants us; art criticism has again left the physiological issues to science. To some degree, Allsop’s work occupies this underexplored area of inquiry. It propels us toward our habits of looking, and asks us to consider the question again: isn’t there an experience to be had that flows through the eyes and into the body and back into space, provoking an undistracted sense of being rooted in time and place? Doesn’t art have the ability to create this situation, however fleeting or idealised it may be?

At first, many of Allsop’s works at Kettle’s Yard appear inert. Black or cream, geometric, made out of acrylic or some other manufactured material, like video tape. If you approach them as material, or as an object, it’s easy to grasp what they are and how they are made; all this is transparent. Backs of works are the same as fronts. Hanging devices are on the outside, or, in the case of Blind Screen [1998-2004], help determine the work’s shape. In this physical sense, they are “thin”: while it may be interesting to enumerate the details, there is no depth in the object itself.9 And yet, once this baseline has been located, the work begins to fill up again. You notice, for example, that the geometry is symmetrical and systematic, but certain accommodations between outside and inside dimensions make it clear that Allsop takes some decisions intuitively. Most works are not purely flat and openly reflective; there are warps and distorting ripples. In previous bodies of work, Allsop aimed to keep the surfaces dead true, and this often meant devising elaborate backing systems. In recent work like the Reflective Editors, Allsop lets the acrylic sheets they are made from hang unembellished. Even as these are pristine in surface and geometry, they are subject to worldly effects, like gravity. The result is that they register the environment in which they are placed - colour, and effects of light and movement - but do so with all the idiosyncrasies of their specific material. In a similar way, the video tape in Blind Screen is drawn as taut as possible, and the accumulation of horizontal stripes makes a nearly continuous surface from top to bottom, that reflects back its particular environmental effect. There is a sense of duality in these works, of resolute materiality, and of sensual activity occurring on their surface [and via their high reflectivity, in the space just in front of the surface].10

It may be best, however, to approach Allsop’s work through photography rather than painting. The Reflective Editors grew out of a series of lith film screens Allsop made to fit over a camera lens. These are similar to the halftone screens used in commercial printing, and held by an apparatus some eighteen inches in front of the camera lens [this length determined by the minimum focal length of a macro camera lens], they produce highly abstracted photographs of natural colour and light. For his 2002 exhibition at the Southampton City Art Gallery, Allsop compiled a group of these photographs into a unique publication: a 44-page colour folio of full-bleed images with no accompanying text.11 Looking at the photographs in this book is remarkably similar to perceiving Allsop’s physical works: they can be read as a surface pattern of black and saturated colour, and [if you half close your eyes] as a justrecognisable landscape.

Allsop’s interest in creating this mediated experience of the physical world reflects a historical connection between optics and drawing, which come together in photography as a set of mechanisms that objectify vision.12 His perennial use of the horizontal rectangle in his wall works suggests a fundamental connection between the side-by-side placement of our eyes and the orientation of conventional representations of landscapes. The Reflective Editors, as gridded or lined screens, organise sight and visual experience, even though you see what they reflect back into your own space more than what they potentially frame.13 At Kettle’s Yard there is the work, One Round Hole, a gloss black vinyl circle with a hole in its centre, applied to the glass of the street-side window, head-height. It invites you to look through it out onto the scene passing by.14 This work clearly relates to the aperture of a camera, and creates a monocular view and the attendant experience of perspectival space; and yet the set-up right up against the pavement and street doesn’t allow for an undisturbed picture of a static, classical landscape. Allsop’s reliance on photographic mechanisms - whether because of their “infra-slim” quality or their connection to conventions of observation - helps clarify his particular approach to making work that would otherwise be called painting, or sculpture, or “installation.”

I began this essay with Sartre, not only because his writings provide a way into the

complexity of subjectivity, but because of the uncanny relationship between his keyhole and Allsop’s work, One Round Hole. I imagine placing my eye against the work’s aperture would provoke a similar experience to the one Sartre describes: my bodily awareness falling away as I become my act of seeing. The work lets me be totally self-oriented as I look out, to represent the picture I see as originating with me. But it seems just as likely that someone might look back at me, eye-to-eye, and if this occurred, I might too be in the other half of Sartre’s story, and find myself at the end of another’s look. It should be clear that Allsop’s work is not an illustration of these ideas, but an embodiment of his parallel interest in particular, sensual, and self-reflexive visual experiences. What is remarkable perhaps, is that Allsop’s works produce both pleasure and knowledge; these things, of course, are not opposites, but two sides of the same issue.

from: Douglas Allsop at Kettle’s Yard [exh. cat.]. Cambridge, 2004

1 Jean-Paul Sartre, “The Existence of Others,” Being and Nothingness [New York: Simon & Schuster, 1956], p. 348.

2 This is a fundamental concern of phenomenologists, from Heidegger to Husserl to Merleau-Ponty: the presence of others is integral to any concept of the self. Phenomenology entered art criticism in the late 50s and early 60s, and was used to explain works whose starting point was the maker’s “subjectivity.” Robert Klein characterizes this approach in his essay, “Modern Painting and Phenomenology” [1963], Form and Meaning [New York: Viking, 1979], pp. 184-199. Allsop considers himself closer to Rosalind Krauss, who argues that the [false] belief in this “primordial spatiality” is “phenomenology’s unconscious.” Krauss, The Optical Unconscious [London and Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1993], pp. 217-18.

3 Allsop belongs to an unenviable group of artists whose work rests against the grain of histories and theories used to explain the art of the last thirty-odd years. His exhibition history reads as a list of inadequate style categories, from neo-constructivism and neo-concrete art to the monochrome. All of these generalise too much, or suggest a connection to historical work based on resemblance.

4 In an essay on Allsop, Stephen Bann describes this historical situation as: “the immensely self-confident internationalism which was taken for granted at that stage when kinetic and optical art succeeded in renewing, and giving popular appeal to, the typical vocabulary of geometrical abstraction.” Exh. cat. Douglas Allsop [London: Laure Genillard Gallery, 1990], n.p. Allsop finished art school in 1963 and began his career as a colour field painter.

5 It is not incidental to my discussion of Allsop’s work that Merleau-Ponty was influential in supporting the idea that advanced art was a better place to look than science for understanding vision. This was the subject of his two major essays on art, “Cezanne’s Doubt” [1945] and “Eye and Mind” [1961]. In the latter he argued that modern science approaches vision wrongly, breaking it down into parts or developing models for how the eye works; painters on the other hand know that vision is something intuitive and embodied. Cezanne “wanted to depict matter as it takes on form, the birth of spontaneous organization. He makes a basic distinction not between ‘the senses’ and ‘the understanding’ but rather between the spontaneous organization of the things we perceive and the human organization of ideas and sciences.” Merleau-Ponty, “Cezanne’s Doubt,” in Sense and Non-Sense [Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1964], p. 13.

6 William C. Seitz, exh. cat. The Responsive Eye [New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1965], p. 7.

7 Seitz, p. 43.

8 The Responsive Eye was a pivotal exhibition for the history of abstract art in the 1960s. Ann Reynolds has recently written about it at length in her book, Robert Smithson: Learning From New Jersey and Elsewhere [London and Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2001], pp. 46-55. There is an enormous literature that theorises and historicises vision; see for example: Teresa Brennan and Martin Jay, eds. Vision in Context: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Sight [New York and London: Routledge, 1996].

9 This aspect of Allsop’s recent work is a shift from his previous interest in “thickness”. For his 1994 installation, Fast Surface [1993-2004] at London’s Chisenhale Gallery - a large projected photograph in the darkened gallery - Allsop wished to make a work that was physically absent.

10 Allsop has cited a term belonging to Duchamp - the “infra-slim” - as relating to these “thin” works. Duchamp used the term in a 1945 poem, and is said to have explained that “the sound or the music which corduroy trousers, like these, make when one walks, is pertinent to infra-slim. The hollow in the paper between the front and the back of a thin sheet of paper.... I believe that by means of the infra-slim we can pass from the second to the third dimension.” Quoted in Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson, eds. The Writings of Marcel Duchamp [New York: Da Capo Press, 1973], p. 194.

11 Allsop also exhibited the lith screens in this exhibition, in a horizontal display case.

12 Lenses emerged from scientific inquiries into the eye’s function; the camera obscura was used as a tool for representing three dimensions in two. Some of the early devices that preceded the modern photographic camera - like the phenakistiscope and the zootrope - bear an odd relationship to Allsop’s Reflective Editors. See, for example, Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century [London and Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1990], chapter four. The photographic technology Allsop’s work relates to is mechanical, and pre-digital. Photography was always about tricking the eye into believing its version of reality; digital photography tends to be about the production of a manipulation that appears photographically real.

13 Again, Fast Surface bears note: the photograph was of the outside of Chisenhale Gallery, rephotographed through a horizontal screen. In effect, Allsop brought the outside in, but by passing it through a screen, it was not a picture, rather an experience of colour, light, and space. The screen has been made into a postmodern trope par excellence by Krauss in her re-reading of Lacan’s well-known essay, “What is a Picture?” She reconfigures light from the clarifier to a displacer of the self: “Light, which is everywhere, surrounds us, robbing us of our privileged position, since we have no unified grasp of it. Omnipresent, it is a dazzle that we cannot locate, cannot fix. But it fixes us by casting a shadow.” Optical Unconscious, op cit., p. 184. Allsop described that in Fast Surface, one point of instability and movement was the shadows cast by people walking through the space.

14 Duchamp made an appearance again in discussions with Allsop about One Round Hole, out of which emerged the title of this essay. In The Large Glass [1915-23], the Oculist Witnesses are the three circles in perspective on the centre right side of the Bachelor section. In the Green Box Notes Duchamp called them “weight with holes.” Writings, op cit., pp. 63-4. More evocative is Allsop’s source, which draws out the connection between the oculus and the male sexual organ: “ With the Splash the series of bachelor operations proper come to an end. The liquid jet rockets upwards through the Oculist Witnesses, as a ray of light goes through the pupil of an eye.” Marcel Jean, History of Surrealist Painting [London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1959], p. 103.

Wolfgang Vomm - On the Opulence of the AustereΛ top

This is what first catches the eye:

The perfect, but cold mirror finish of industrially produced materials [film, acrylic sheet], then the stringent arrangement of systems based on simple geometric forms and finally the absence of colour, of anything identifying, emotional or personal in favour of a strict rationality. Granted, on first sight it is a frosty and in its perfection, clean world which one enters, a polar world between black and white, a strictly defined world of measure and order, a world seemingly without secrets or surprises. Everything is rational, transparent and lucid. Proportion, number and order are categories that appeal to reason before our senses are stimulated to go on a journey of discovery.

And another thing one notices immediately:

Douglas Allsop rejects all dramatic gestures, explosive colours and elaborate material outlay. His art comes into view quietly, it is introverted and rather static. With these characteristics it appears to consciously set itself against the turbulent chaos and the noise of the trivial that surrounds us. It is created with minimal means which are employed in a way that all operations carried out by the artist are instantly recognizable and verifiable. By what it has renounced the work achieves concentration. Although it is spiritually akin to Minimal and Conceptual Art, it occupies an independent position, which is characterised inter alia by the deliberate spatial relationships of many works and the integration of the optical phenomena resulting from this.

What now is special about these works, what causes the quiet sensations with which Allsop surprises us?

No doubt there may be viewers who conscientiously but briskly take the measure of the works without seeing anything. Real seeing can only be experienced by those who take their time and open their minds because with all of these works the viewer becomes part of the work in a certain sense; they can only achieve comprehension if they are prepared to be active and to maintain their observation whilst they move about the space.

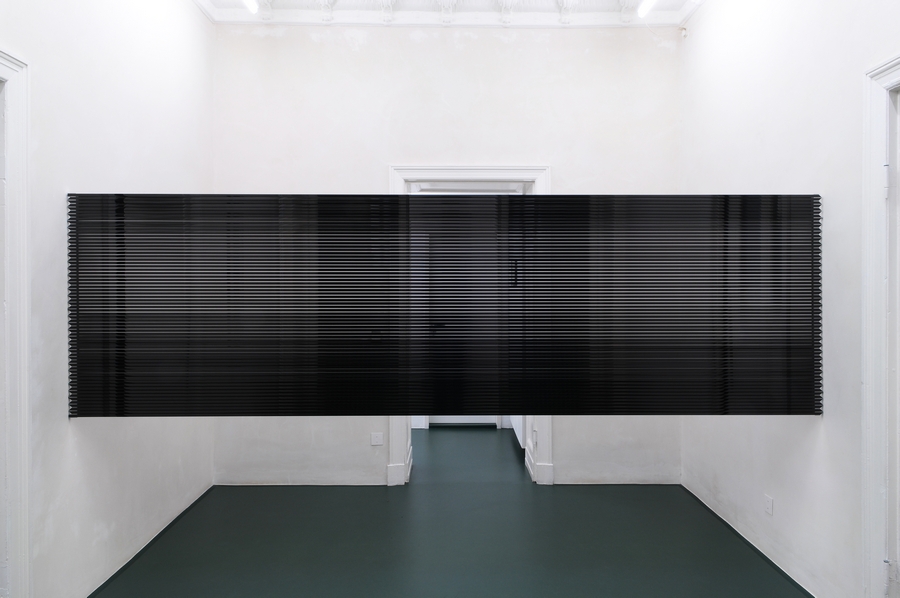

In this respect the large work “Blind Screen” [Ill. pg 6-7] is exemplary. Specifically made for this exhibition the work takes into account the existing situation of a bay window as a polygonal extension of the exhibition space. Allsop has blocked the entry to this space with a screen of videotape. The black videotape is stretched horizontally so tightly in two layers from wall to wall that the parallel arrangement of the tapes call to mind a venetian blind. This arrangement results in a startling phenomenon that, however, only reveals itself to the viewer if they not only change their position in front of the work but also their eye level. The high gloss material of “Blind Screen” is experienced as a spatial boundary obstructing the viewer and not letting them see or enter into the space behind the screen. But by only slightly changing position another experience can be had: the effect of a barrier seems to be inexplicably cancelled as looking into the space beyond is suddenly now at least at eye level possible, while the lower parts remain hermetically black and impenetrable. One doesn’t only see into the space behind the opaque film tape wall, optically functioning as a barrier, but also to the windows and finally – to a further layer of reality – the trees and houses beyond. This view of the outside world coming through the narrow gaps between the tapes is partially blurred because daylight flickers across the edges of the gaps. The picture of the outside world subdivided by lines has a peculiar kind of reality which is subject to a further refraction by the fact that the tape screen reflects the exhibition space in front of the bay window. On the level of “Blind Screen” the images can pervade each other or blend with each other, on this level too the viewer is present through his mirror image. The film tape functions here as it were as a barrier and at the same time as a porous membrane between inside and outside. These complex pictorial experiences may be regarded as metaphors for the ambiguities in our perception of reality.

For other primarily multi-part works Douglas Allsop uses acrylic sheet, with a high-gloss reflective surface. The intensity of the reflection depends in part on the colour of the material, as Allsop illustrates with two three-part works [Ill. pg 16 and 17]. With these works three rectangular panels, the dimensions of the traditional panel in painting, are placed next to each other, reminiscent of a triptych. A sequence of colours from left to right starts with black, followed by a transparent, pale green and then clear acrylic. All three panels of both works have a series of 5cm long slots, in uniform horizontal rows in one set, and vertical columns in the other. These openings, through which each panel connects with the wall spatially as well as visually, in that the white of the wall is activated in the composition in varying degrees of intensity, are perceived as a sign system. Seeing the rows of slots one thinks of lines and therefore automatically of typography.

What is exciting then is to observe how under the influence of light the different aspects of the panels and the variation of the viewer’s position changes the presence of this sign system. Its effect on the gloss black surface is not at all uniform. Depending on which angle the viewer looks at the reflecting plane the slots may be practically invisible. From an acute angle of the perspective the surface appears almost untouched. Reflections of the surrounding space with windows etc. contribute to the disappearance of the slots and thus assign to them a passive role. From the front one expects perhaps, due to the regular position of the slots, a uniform effect of the individual signs. However it is notable that the slots on the lateromarginal side are increasingly shadowed and that therefore their effect is considerably modified.

Similar observations can be made looking at the green and transparent panels, where the signs stand out altogether weaker since there is no hard black and white contrast present. Here, too, the white colour of the wall is less evident, instead it is the varying degree of shadow in the spaces created by the slots on whose precisely cut edge the light refracts. In the case of the green panel the colour is intensified at this point. In the transparent panel the recessed spaces are recognisable or perceptible almost solely by the shadows present.

What is interesting and at the same time surprising is the recognition made conscious by these works of Allsop that the degree of effectiveness of the sign sequence does not only depend on the properties of the reflective acrylic sheet but even more intensely on their placement, i.e. their position vis-à-vis the horizontally incoming day light. As the photographs in this catalogue impressively show the horizontal stack of lines stand out clearly and unmistakably from the black ground, while on the transparent panels they are less apparent.

The reverse applies to the line arrangement of the vertical slots. With light coming from the side they disappear completely, but on the transparent panel the shadows make them stand out.

With the traditional panel painting these works have at most the format in common. But they surmount the boundaries of the traditional panel in that they are conceived to actively include the surroundings or rather to letting them be part of the design. They function so-to-speak as catalysts between wall, panel and space while light as a variable force constantly defines and redefines the pictures of reality and its derivatives.

At the beginning the rationality of Douglas Allsop’s works was briefly mentioned. There is no question that mathematics and geometry exert an important influence on his creative thinking and his working method. He is a precise and persistent worker who conscientiously analyses aesthetic problems. All of his works are based on exact drawings which in their meticulousness can seem like notes from a research lab. He knows very well that the simple always proves to be the most difficult and he is not happy until nothing else can be removed or reduced. That applies unequivocally to anything leaving his studio. And this extraordinary high demand for perfection applies also to his outside suppliers who produce the works according to his instructions. Surely for them some of these commissions are borderline challenges.

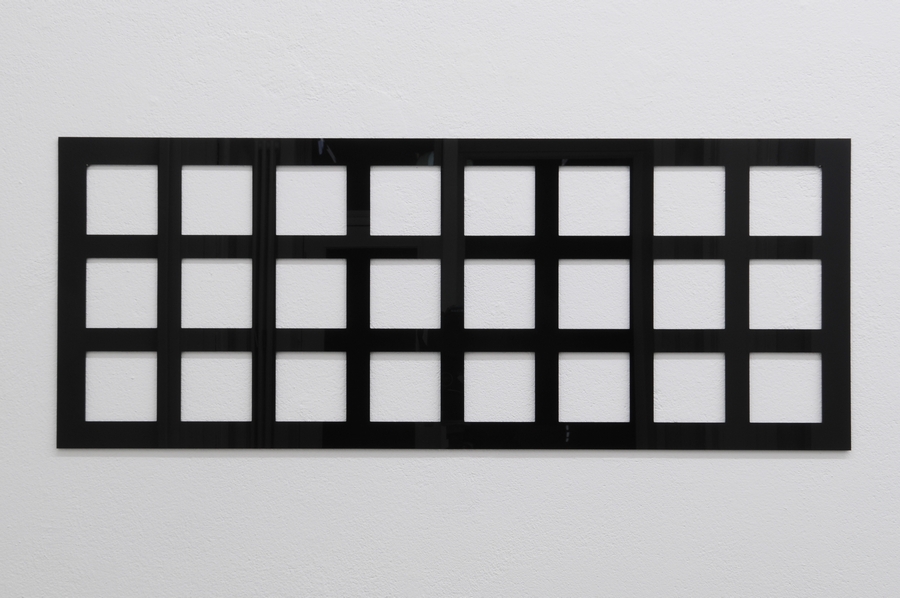

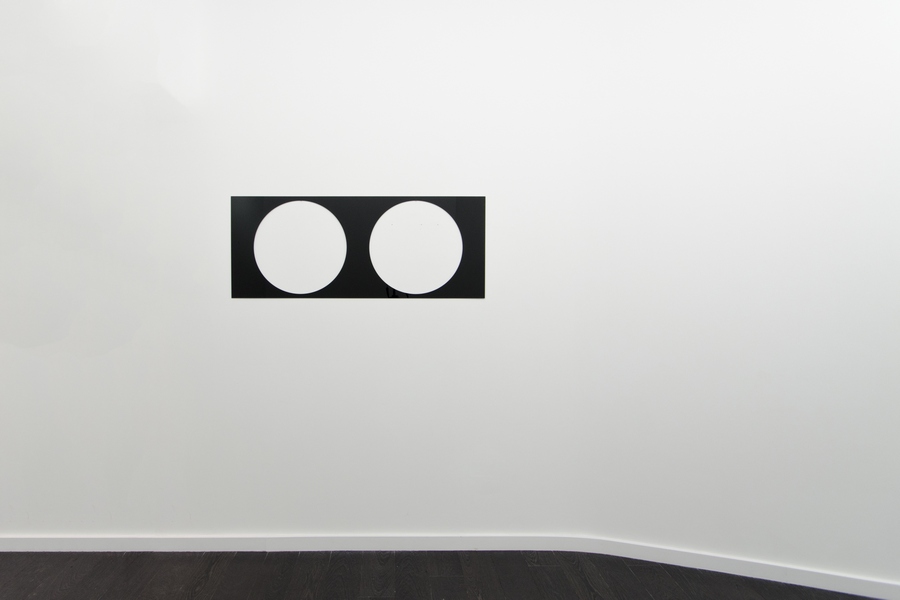

The insistence on precision, perceptible in Allsop’s work, is no eccentric quirk, but an inner necessity resulting from the form. If one looks at the large, almost wall-covering acrylic panels whose surfaces are perforated by a dense grid of 48 x 18 squares or 49 x 19 circles and thereby transformed into fragile nets [Ill. pg 14-15], one realises the challenges which Allsop deals with. In these two works the dialogue is developed further. Wall and panel intentionally form a unit, black and white interlock. Several fundamental questions arise, for instance, what is the relation of the remaining black surface, its measurement now the smaller amount, to the sum of the individual cut-out forms, that is to something that is no longer there? What in any case is experienced as form? Only the black grid structure or in equal measure the white area of the wall demarcated by it? Does it become form or does it remain wall? Or: what is the effect of the grid structures? Does one of them appear more stable? And finally: whether and how these perforated structures are still able to reflect their surrounding as a mirror image? Does the increased attachment to the wall lead to a loss of this aspect? At which point does it no longer occur?

Irrespective of this the viewer considering such an accumulation of stereotypical elements may ask to what extent the eye is able to read a form or if it will loose its orientation and start wandering off - lost.

The works by Douglas Allsop raise in spite of or precisely because of their seeming simplicity many questions concerning creative endeavours as well as general

phenomena of perception. But his works not only raise questions, they also give answers – at least to those who engage with them without preconceived ideas and accord them time.

from: Douglas Allsop – blind screen [exh. cat.]. Bergisch Gladbach, 2008.

Translation from the German by Gunhild Muschenheim

Λ top

![Metatext series. Reflective Editor [4 Diptychs]. 2011/12. Cast acrylic sheet, steel pins, polyester tube, 75 x 30 x 0.2 cm each.](bilder/artists_douglas_allsop_works/DSC_8572_ba_kl.jpg)

![Two single holes, 2013. Detail [View from outside on Blind Screen]](bilder/artists_douglas_allsop_works/DSC_8546_ba_kl.jpg)

![Reflective Editor: Two x 2 round holes, square pitch, 2008. 108 cm Dia. x 0.5 cm [81 cm Dia. centre hole], 108 Dia. x 0.5 cm [135 cm Dia. centre hole]](bilder/artists_douglas_allsop_works/2 x 2 round holes_2008_Weissenstadt_kl.jpg)

![Editor: 9 vertical units, 2012. Granite, 375 x 150 x 30 cm. Cambridge [GB]](bilder/artists_douglas_allsop_works/BC_dAllsop_Cambridge_kl.jpg)

![dr. julius | ap: Anschaungen, 2013. Metatext series: Reflective Editor [4 Diptychs], Reflective Editor: Twenty-four square holes, square pitch [ri.]](bilder/artists_douglas_allsop_views/DSC_8610_ba_kl.jpg)

![Reflective Editor [Diptych]: Twenty-one vertical/thirty-one horizontal slots, 2005. Cast acrylic sheet, steel pins, polyester tube, 100.8 x 72 x 0.3 cm each](bilder/artists_douglas_allsop_views/DSC_8569_ba_kl.jpg)

![Blind Screen, 2013 [ri.], Metatext series: Reflective Editor [2 of 4 Diptychs].](bilder/artists_douglas_allsop_views/DSC_8682_ba_kl.jpg)

![Blind Screen, 2013. Video tape, aluminium profiles, 99.25 x 335.5 x 2 cm. Two single holes, 2013 [shining through].](bilder/artists_douglas_allsop_views/Unbenanntes_Panorama1_ba_kl.jpg)

![Artis engineering, Berlin-Tempelhof: TECH.ART.INTERSECT. Metatext series: Reflective Editor [4 Diptychs].](bilder/artists_douglas_allsop_views/drj045_13_2046_kl.jpg)

![Städtische Galerie Gelsenkirchen: ‘nicht nur Black and White’, 2014. 864 square holes, square pitch 2004. 2 Round Holes [reflection]](bilder/artists_douglas_allsop_views/864 square holes_square pitch 2004 detail_Gelsenkirchen_kl.jpg)

![Galerie Bernd A. Lausberg. Reflective Editor: 10 single vertical, 15 single horizontal slots, parallel pattern [glass look], 2005. 72 x 108 x 0.3 cm](bilder/artists_douglas_allsop_views/10 single vertical_15 single horizontal slots_glass look_2005_Lausberg_kl.jpg)